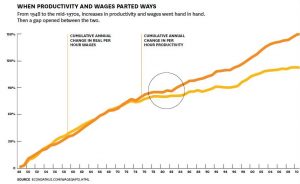

I opened this series of posts on financial markets with a graph showing the dramatic shift in the share of wealth that goes to corporate profits rather than wages, which lies behind the rise of the 1%. Similarly, William Lazonick opens his 2014 paper ‘Profits Without Prosperity’ with a graph showing how wages have grown at a slower rate than productivity. This is showing us exactly the same thing in a different way – wage-earners taking a lesser share of economic growth.

Just as I was asking why the wealth has been increasingly flowing to the richest, Lazonick asks why the population as a whole is not receiving its share of the growing economy. Part of the answer, he says, is corporations using their profits to buy back shares.

Lazonick studied the use of profits by all 449 companies that remained in the S&P 500 index from 2003 to 2012, and shows that a staggering 54% was used to buy back shares. Why would they do this?

In the paper he outlines the reasons given to justify stock buybacks and then refutes these based on his research. It would take too long to summarise all these points here – but the paper itself is just 8 pages and very clearly written.

The real reason, Lazonick says, is the link between executive pay and share price. Buying back shares is boosting share prices and thereby boosting the bonuses of corporate executives.

You can see why I would be interested in this phenomenon. In earlier sections of the blog I highlighted my lack of faith in the efficiency of financial markets, and in this section we’ve followed the money flowing to profits rather than wages and found it concentrated in huge institutional cash pools. I’ve shared with you Pozsar’s empirical research showing how the investment behaviour of these pools has destabilised financial markets – asset prices are wildly inflated while the real economy stagnates through lack of investment in productivity.

Last week I gave a detailed explanation of quantitative easing, showing how this government policy has had the same effect – inflating asset prices without channelling funds to investment.

And now we see the same dynamic again, this time caused by corporate decisions to buyback shares – inflating share price while depriving the economy of funds for investment.

Next week I will start pulling all these threads together, drawing out the tentative conclusions I feel we can be draw about financial markets. But I want to conclude this week with a note of caution…

My purpose in introducing Lazonick’s work is to highlight from a fresh perspective the dynamic that I’ve been describing for several weeks now. I happen to have huge respect for Lazonick – I find his work to be meticulous in its attention to empirical evidence, and have several of his books and papers near the top of my current reading list. It’s also worth noting that his paper was published in the Harvard Business Review – this is about as mainstream as you can get, not some radical fringe publication – and the article actually won the HBR McKinsey Award for oustanding article of 2014.

But unlike most other subjects tackled in this blog, I haven’t delved deeply into the particular issue he presents (share buybacks). For a different perspective, take this paper by Alex Edelman, ‘The Case For Stock Buybacks‘, also published by HBR in 2017. He makes some clear points about why buybacks can be justified, which are not simply ideologically driven polemics so common in the economics mainstream. Indeed, it is clear from his areas of research that he is far from being a neo-liberal defender of the status quo. But even though he references Lazonick’s paper he doesn’t directly address any of Lazonick’s arguments. And ironically, some of Edelman’s arguments are refuted by Lazonick, even though Lazonick’s is the earlier paper (Lazonick refutes the typical arguments in defence of buybacks, and Edelman ends up making the same arguments without addressing Lazonick’s refutations).

My inclination is to trust Lazonick’s conclusions more, but I always want to guard against simplistic conclusions drawn without fully exploring all the evidence.