This is the final post in the blog (for now at least). After over 3 years, 96 posts and 140,000 words, I’ve sketched out some preliminary thoughts!

The economic analysis in the blog points to a role for government, and this section (on ‘Political Economy’) has addressed why, in contrast, the prevailing belief is that governments should stay out of the economy and leave it to free markets (a belief now being challenged by the current crisis). I have suggested that we have to learn, as a society, precisely what the government’s role is and how it can play it effectively.

Last week I suggested a founding premise, based on scientific fact, for such a process of societal learning – the oneness of humankind – and pointed out that this is not just some nice thought or vague platitude, but that it has profound implications for how we approach justice and economic life.

In this final post I am going to point out certain indisputable economic facts that should then form the starting point for a process of learning about the economy itself. When I say indisputable, mainstream economists would dispute them! And that is somewhat confusing, because they are all very straightforward, logical points. Indeed, I believe the points below are based on incontrovertible empirical facts and rational analysis. You can read them yourself and make up your own mind.

Most of these points are explored in detail in the blog, but as I have often mentioned in the past, I didn’t begin this blog with a grand plan of what I wanted to say. My work as a manager in an anti-poverty programme had left me with certain questions about the economy. When I quit the programme in disgust at its gross failings, I then started studying economics looking for answers to these questions. As described on the ‘About’ page, I was shocked by what I discovered. Mainstream economics is ideologically driven pseudo-science, merely serving as a justification for the dominant political philosophy, and indeed for the gross economic injustice and inequality in the world. I also found that a dispassionate analysis of the actual empirical reality of how the economy functions was interesting, indeed beautiful, and something that I believed most people could understand if it was presented in clear and straight forward language.

So I therefore began the blog as an experiment to see if I could clearly convey what I had discovered, while I continued my studies. And I absolutely failed in this experiment – the blog is filled with technical detail that becomes impenetrable to all but the most interested reader. However, the act of writing has clarified my own thinking and has now laid the results of my study clearly before me (I often come back and read my own blog when I’ve forgotten details, because it does in fact contain some of the most clear and precise descriptions available to me on some of the complex themes covered). This in turn has served as a foundation for my further studies – there is a whole other layer to add on top of what is on the blog so far!

Right now, however, I have no motivation to continue writing. The current crisis is revealing so much about the economy that I may come back and add a section on what can be learnt. And I may eventually come back and write a few posts summarising the analysis and conclusions, essentially completing what the blog was originally intended for: to describe how the economy functions in clear and straight forward language, such that anyone could read it and understand how we can create an economy that provides enough for everyone.

For now, this summary of these facts about economic life that should be the start of any effort to understand the economy will have to do. These facts are:

- No business can begin without credit, and therefore decisions about the allocation of credit – who to allocate it to and for what purpose – are fundamental to the path the economy takes.

- Therefore, the functioning of financial markets (whose purpose is to allocate credit) is critical to the functioning of the economy.

- Money itself is a form of credit, and therefore it is essential to understand the monetary system and to create one that allocates newly issued money in the most effective way.

- Production, trade and financial markets now operate across national borders, and therefore the currency of international trade and the system behind it have a unique importance and must be understood; the present system has evolved haphazardly, and the relevance of lessons from national monetary systems is only now beginning to be dimly recognised.

- The distribution of income affects how money flows around the economy, determining which businesses thrive and which do not, and therefore which industries can raise funds for investment and which cannot.

- Innovation is one of the most significant factors in how the economy develops and therefore any meaningful study of economics must include an empirical, historical study of how innovation happens and the development of an associated theory.

- The economy is a highly complex, dynamic system, constantly changing and evolving (largely as a result of innovation); the study of the economy should therefore utilise the approaches of systems theory. This complexity makes ‘fundamental uncertainty’ an integral part of economic life and economic models should take account of this uncertainty, not assume it away.

1. Credit

As this early post points out, no business can begin without credit. You need to spend money to set up a business in the first place, and the business itself cannot earn money to spend until it starts trading. Hence, the opening section of the blog proposed the following as a fundamental proposition:

Decisions about who to allocate credit to, and how much credit to allocate, are absolutely fundamental to the path the economy takes in the future.

Mainstream economics simply ignores credit. Its argument is that if I borrow off you to lend, the money still gets spent into the economy. It makes no difference who spends it. This is completely wrong for several reasons, but 2 are particularly relevant here:

1) Most fundamentally, if the allocation of credit is what determines the future path of the economy, then those who make these decisions have incredible power. For example, the future of life on our planet literally depends on whether we develop sustainable sources of energy, and this in turn depends on the extent of credit made available for research and development into both the production of such energy and the utilisation of it. As it stands, the present system is failing us.

2) If I directly invest my own capital into my own business I am not committed to making repayments. But if I borrow to make that investment, I have to make regular repayments dependent on the type of financing. If I borrow at a fixed rate then I’m highly vulnerable to inflation – low inflation or negative inflation increases the value of my debt in real terms, high inflation reduces its value (but correspondingly hurts the lender). If it’s a variable rate loan then I’m highly vulnerable to interest rates. The fact that the funding is credit makes a difference.

This last issue draws out a final important point to make about credit. I’m using the term loosely to effectively mean “advance funding”. “Financing” might have been a more precise technical term. A business can raise finance by taking out debt or by selling shares, and from the business accounting perspective these shares are not debt, they are equity. The business is not committed to making repayments until they make a profit. We will return to this distinction below.

But the essential point to understand is that the allocation of credit to productive investment in industries necessary for a our future well-being is an absolute prerequisite for a healthy economy. It is essential that a legal and regulatory structure, and even direct government intervention, ensures that credit is so allocated. And this therefore brings us to…

2. Financial Markets

If credit is the starting point of economic activity, then it follows logically that the functioning of financial markets is likewise critical to the economy. And mainstream economics ignores these as well, for the same reason that they ignore credit. Prior to the great financial crisis, mainstream models of the economy did not include banks or financial markets at all. Now they have started to introduce banks as a “friction” in their models. It’s pathetic. I’ve regularly made the point that the term “shadow banking” creates a sense that financial institutions were somehow hiding in the “shadows”. And while it is true that some of the instruments now termed shadow banking were created to avoid regulation, banks were not attempting to do it in secret. Economists simply ignored what was going on because they believed financial markets were irrelevant – that they merely shift money around in an efficient way so that savings ended up being spent back into the economy. And how wrong they were proved to be.

Financial markets matter, and there’s a whole section on them in the blog, focusing specifically on empirical research that illustrates how effectively (or not) they are channelling funding to productive investment. Even though there is so much more I could add now, the conclusion would remain the same: that currently financial markets are grossly inefficient and dysfunctional. At the moment, ever greater amounts of wealth are siphoned out of the real economy into financial markets, increasing demand for financial assets and therefore inflating prices into bubbles.

We are in a bubble right now, by the way – many financial commentators refer to it as the “everything bubble”. Viewed from a long-term perspective, no financial asset is currently worth its face value because there has been a lack of investment in the long-term productivity of the economy. Instead of investing their profits in productivity, the largest multinational companies store them in financial assets. What is worse, they inflate these profits by evading taxes, and then purchase government bonds as a safe store for these retained earnings, and thus in the process get paid for avoiding their taxes.

I am explicit in the blog on the need for government intervention in financial markets to ensure that saving is channelled to productive investment. It is also interesting to note that the father of modern capitalism, Adam Smith, himself decried the wasting of wealth on unnecessary luxuries rather than investment in business. And all those free marketeers, who obsess about individual liberty and are so so fond of misquoting Smith’s statement about an invisible hand, would do well to heed Smith’s own words in The Wealth of Nations (Book II, Chapter II) on the regulation of financial markets:

“Such regulations may, no doubt, be considered as in some respect a violation of natural liberty. But those exertions of the natural liberty of a few individuals, which might endanger the security of the whole society, are and ought to be, restrained by the law of all governments; of the most free, as well as of the most despotical. The obligation of building party walls in order to prevent the communication of fire, is a violation of natural liberty, exactly of the same kind with the regulations of the banking trade which are here proposed.”

I have done so much more reading since writing this section of the blog, there is much more I could say and much more compelling evidence to present. But much of this revolves around the most important of financial assets…

3. Money

Money is a type of financial asset. The section on money describes how money is currently created in the modern economy, why this causes a problem and what needs to be done. In particular, there is an absolute need for the government to fund a deficit every year by creating new money. This is sometimes called “monetising the debt” or “monetary finance”, and if you read the financial news you’ll see people repeatedly talking about the latter as a way to fund economic stimulus in response to the coronavirus crisis.

This all links to the discussion of equity above. I’m not going to attempt to fully explain this now, but this article on the World Bank blog makes the argument that government created money should be accounted for as equity, not debt. Money is literally a form of share certificate entitling the owner to part of the produce of society. It is not a tool for acquisition and competition, it is a tool to enable sharing within society. It ties us all together in the reciprocal relationship in which we benefit from organised, orderly, productive societies, that we in turn help to create through the contribution of our talents and capacities.

My further studies since writing about money on the blog have greatly extended what I could say about this subject. I now see clearly how critical it is to understand exactly what money is. This can best be achieved, I believe, by tracing the history of its development and identifying the myths about money that have built up along the way. These myths are so ingrained in our society that we need to actively root them out before we can think about money in a clear and logical way. What we will then see is that money is created by both the state and the private sector. There has never been a system of universal, standard currency that was not, ultimately, backed by the state, but the monetary system evolves from this foundation through the actions of the private sector. We are conditioned by the current political discourse in society to feel a need to dichotomise and believe that it should be one thing or the other, but in fact we need to recognise that money is, in fact, a hybrid system.

This way of describing the monetary system is based on the work of Perry Mehrling, who is perhaps the pre-eminent exponent of this fact-based analysis of money, and his work is briefly summarised in two posts starting here. I have also recently discovered the wonderful papers of Carolyn Sissoko, who always seems to pick the most incredibly interesting aspects of monetary history to analyse. Vital lessons can be drawn from her work on late 19th century money markets in London, for example, or the evolution of universal banking in the 20th century.

These lessons of history highlight the essential role of the state in the monetary system. But how does this work on a global level? This leads to the consideration of…

4. Foreign Exchange

I originally wanted to write a section on foreign exchange, but when I saw how long, detailed and technical the blog was becoming I realised that such a section would extend to dozens of technically impenetrable posts. My continued studies have abundantly confirmed how critical this subject is.

Indeed, when we talk loosely about financial markets, we basically mean international money markets, and therefore markets for US dollars. The currency of international trade is the US dollar, and most institutional traders are focused on the dollar price of financial markets. After the Brexit vote the British stock market rose, but not because investors were now confident in the British economy. In fact, the value of the pound had fallen because of a lack of confidence in Britain as a result of that vote. The British stock market had similarly fallen if priced in dollars, but the fall in the value of the pound made it look like it had risen if you looked at the price in pounds. The point is, the sterling value was basically irrelevant – all that matters is the US dollar.

The dollars used in international trade are not actually held in US-based banks, and are known as eurodollars, with London being the biggest eurodollar money market. This system has evolved gradually since the Second World War, with little in the way of planning or oversight. Indeed, you often find people writing as if the system is completely in the dark and not understood. This is not actually true, it’s just that mainstream economists have completely ignored it. It should have been their job as scientists to study it.

Recent publications shine a clear light upon it, drawing upon historical sources and demonstrating that the information was always there for the genuine economic scientist to research. Notable among these is this paper by Braun et al from March this year, on the role of central banks in the development of the eurodollar market in the ’70s; this paper by McCauley and Schenk, also published in March (I told you these were recent), on the use by Central Banks of foreign currency swaps as early as the 1960s to manage eurodollar liquidity; and the 2015 book Bonds Without Borders: A History of the Eurobond Market by veteran bond trader Chris O’Malley, who lived and worked through that history. Alongside these must be studied a host of recent papers on repo markets, including Gabor, Gabor and Ban, Sissoko, Adrian and Shin, anything by Zoltan Pozsar (who has produced too much to link it all) or Nathan Tankus. In addition, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) is an invaluable source of papers and bulletins.

In these days of interconnected global trade, in which the components of most products are manufactured across a number of countries, the foreign exchange system is central and critical to the functioning of our economy. No economy can function without access to US dollars to purchase essential imports, including food and oil. Hence, the capacity of an economy to earn US dollars through its exports places an absolute constraint on its capacity to grow. This is known as the balance of payments constraint, a concept first identified by Nicholas Kaldor, and described in the blog here. This 1978 essay by Francis Cripps is a particularly good explanation.

You cannot have an intelligent, informed opinion about the economy if you do not understand the functioning and impact of the foreign exchange system (a statement which, if true, has brutal implications for all mainstream economists). The great financial crisis was a crisis in dollar funding markets based in Europe. The US housing crisis was the trigger but not the cause – the markets themselves were so dysfunctional that they were just waiting for some upset to trigger a collapse.

The US Federal Reserve belatedly realised that it needed to backstop the eurodollar system. It learnt from this, and at the onset of the coronavirus crisis quickly took steps to prop up the system again.

But not nearly enough was learnt in 2008 – these markets continue to be highly dysfunctional and the coronavirus crisis is the mother of all triggers! It is already exposing the reality of these markets and this time it is essential that society does not fail to analyse adequately and learn sufficiently. The latter part of this recent post outlines some of the implications (with a number of useful references).

Ultimately, the whole world has to ask itself whether it wants the US Federal Reserve, with its Chair appointed by the US President, acting as the de facto central bank for the currency of global trade. As the post just linked above states, we need a new system. I may choose to come back and write about this in the future, but for now I have a mountain of reading on this subject to gleefully throw myself into now that I’ve finished the blog.

5. Distribution

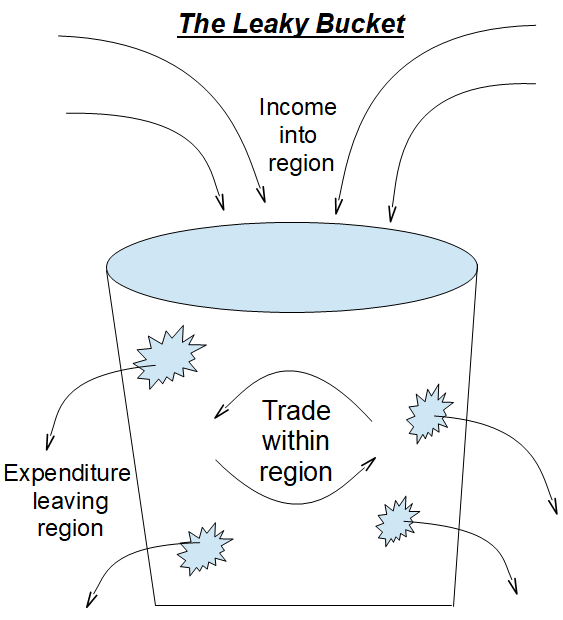

One of the issues that had become obvious to me working in an anti-poverty programme is the critical importance of the distribution of income to the progress of the economy. There is a well-known analogy in community regeneration known as the “leaky bucket”. Income earned by individuals and businesses in a local or regional economy represents water pouring into the bucket. They will either spend that income on businesses within that region, representing water circulating within the bucket, or they will spend it on businesses based outside that economy, representing water leaking out of holes in the bucket. Hence we get this diagram:

Basically, if more money leaks out than pours in, the region will get poorer. It doesn’t matter how much regeneration funding the government spends, if they don’t examine and address the flows of expenditure within the region in question and ensure that the funding doesn’t leak straight out again, poverty in that region will inexorably increase.

When we step back and analyse the economy in this systemic manner, we start to see it in a new way, one that is essentially about flows of wealth. And hence when I quit my job I was interested in learning about the flows of money in society and the monetary system. This has led to everything described under the previous sub-headings! But addressing the question of distribution directly, a second foundational concept of the blog highlighted in the first section is:

The distribution of wealth is critical to the future path of the economy.

Mainstream economics usually argues that distribution makes little difference. One way or another, the money is spent into the economy, and the economy doesn’t care who spends it. This totally ignores the impact of the fact that people with different incomes spend their money on different things. In addition, if a region is hit by the closure of a major industry then all the businesses in that region will feel the impact of the resulting fall in expenditure (back to the leaky bucket analogy).

Hence, economic policy has to address distribution – it is not just an effect of the functioning of the economy, it is actually one of the major causes of the path it takes. And this is before we consider the astoundingly dramatic social impacts of wealth inequality on all members of society, as described in Wilkinson and Pickett’s seminal work The Spirit Level, easily one of the most important books published so far this century and summarised in the blog here.

In the ‘Distribution’ section of the blog I do my best to expand on this. However, I never felt I’d quite captured what needs to be said, and actually point out my dissatisfaction with my lack of knowledge of empirical studies in this area in one of the posts (a post that serves as a summary for the entire section). Then just recently I read about Michal Kalecki’s model of effective demand and income distribution. To my surprise, it ties what I was trying to say in the Distribution section with my observations in the ‘Productivity‘ section on the role of retained earnings (business saving) in funding investment (see this post for a summary of that section).

In brief, as long as businesses are making sufficient profit to fund investment (or attract external funding), any reduction in wages will reduce aggregate demand and slow the economy, making everyone poorer. There is an optimal wage rate relative to profits to both sustain demand and ensure adequate funding for investment. Knowledge of this, based on empirical studies, could and should provide a guide for the management of the economy. The next step for me is to explore empirical research into this theory and see how this refines my understanding of the theory and of the functioning of the economy. This will come after my further study of the eurodollar system. I don’t believe this study will ever end – the discovery of new knowledge simply opens up new paths of inquiry.

6. Innovation

I stated above that financial markets need to channel savings to productive investment, rather than simply soaking those savings up and inflating asset price values. But investment funding is not sufficient for economic development, we need innovation – new products, new technologies and new methods of production.

Nothing could be more ubiquitous to humanity’s economic life, particularly in the modern age, than constant innovation and development, leading to growth and greater material prosperity. Of course, for environmental sustainability we need to break out of the paradigm of continual growth. But therefore we need innovation in green technologies. And we need innovation in modes of production and distribution that do not require some populations to work 12 hour days for subsistence incomes. We need increases in productivity to lead to the production of the same amount of stuff utilising less labour hours and less energy, not the production of more stuff because we keep up the same insanely high level of inputs.

The lack of research into this by mainstream economics is frankly astounding. What could be more central to a true “science” of economics? Instead, innovation is treated as an “exogenous shock” in their models – it’s something that happens mysteriously, outside of the system, disrupting the equilibrium.

However, there is considerable research into how innovation happens, learning from the laboratory of history. Creating an economy that provides enough for everyone will require us to learn these lessons. The systems of innovation literature, described two posts ago, is a great place to start, as is the work of Erik Reinert and Mariana Mazzucato. Indeed, there is so much research on this subject that it’s another area that I need to study in much greater detail.

What this research reveals is that the government has a critical role to play in creating the right conditions that foster and encourage innovation. Industrialisation has always been the result of a conscious government industrial policy, in every country in the world. Similarly, all the major technological breakthroughs of the modern era have occurred as a result of government funding for research, infrastructure and business development. If you don’t believe me, read the posts linked in the previous paragraph, and then follow up the references.

A major theme of this section of the blog, however, is that this does not mean that we need soviet-style “command economies”. The analogy I repeatedly use is that the role of the state is to be like a gardener, not an engineer. It needs to create the conditions that promote innovation, stimulate the development of industry suited to the circumstances of the nation, and tend and nurture the resultant growth. This includes ensuring an efficient flow of credit to productive investment in the necessary industries, and also a distribution of income that ensures adequate demand for a range of projects across all regions, as addressed in the previous sub-headings. But the role extends far beyond this, as the the summaries in the posts linked above make clear. For a more detailed use of this “gardener” analogy see here, here and here.

Obviously, this role for government is not something we have experience of in modern global society. Indeed, as I keep saying, now that we so desperately need competent government intervention to steer us out of the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus lockdown, we are going to pay the price for 70 years of free market ideology that has led to a complete atrophy of the necessary skills of governance.

Hence we now need to learn, as a society, about the role of all sectors of society – individuals, communities, businesses and the institutions of the state – in creating a functioning economy that provides enough for everyone. This is essentially a process of learning, and I therefore discuss the application of research on learning organisations to the economy as a whole here and here.

7. Complex Systems and Fundamental Uncertainty

If you know anything about economics, then you will know that central to all mainstream economic thinking is the idea of “equilibrium”. If we just leave everything to the unregulated free market, the laws of supply and demand will cause those markets to reach “equilibrium” at the point that provides greatest “surplus value” to society, maximising “utility”. (Excuse me, I just need to go and wash my mouth out.)

This is not the place for a detailed analysis of general equilibrium theory, its grains of truth and fields of error. But I feel it is a self-evident fact that economies are dynamic complex systems that are far from equilibrium. The forces that may tend to lead to equilibrium are constantly disrupted by new innovations, new consumer trends and by the uncertainty of the financial system. The field of economics would therefore do well to model itself on the study of complex systems. This post provides a brief introduction to the relevance of systems theory to the study of economics.

With such volatility and complexity comes unpredictability, and hence it seems uncontroversial to suggest that uncertainty is an outcome of this system. But in addition, the fact that we all live in a world of “fundamental uncertainty” directly affects our behaviour and choices within the economy. Uncertainty is actually a cause of the complexity of the economy, as well as being an effect of it.

The significance of this is not easy to grasp, and first of all you need to understand that in mathematics there is a difference between “risk”, in which numerical probabilities can be reliably assigned to future events, and “uncertainty”, in which we simply do not know what the likelihood of different outcomes is. This is explained in more detail here. The fact that all people, both consumers and businesses, do not know what the future holds is a significant factor in their decision-making. This may seem a trivial point, but mainstream economics actually assumes that people have all full and relevant information in making their decisions, and thus assumes uncertainty away. This is why it is necessary to point out that we live in an uncertain world!

To illustrate the importance of uncertainty, I’m going to consider the differing government responses to the coronavirus. Those countries that locked down tightly and early suffered relatively few deaths, relatively little impact on their health systems, and are now able to begin “unlocking” and focus on getting their economies going again.

Those countries that were resistant to locking down (typically because of their quasi-religious fundamentalism around the issue of individual freedom) now face the galling prospect that they will need to have a longer lockdown because the disease is still rife within their countries. The future for their economies is bleak indeed.

Yet the simple fact is that the evidence did not exist to prove the need for a tight and early lockdown. There have been very few international pandemics from which to derive clear, scientific, empirical evidence of the best response. In addition, it is very difficult to study how viruses spread because we are typically not aware that transmission is happening at the moment it takes place (or else we would prevent it). So a lot of of what we believe about virus transmission is supposition and inference. Add to this picture that this is a new virus about which little is known, and the evidence base just did not exist to give high confidence about any specific action. We are uncertain about many details of this virus.

And hence Sweden also got caught out. It famously did not enforce a tight lockdown, and its mortality rate has been much higher than neighbouring countries. That it is not as high as countries like the US and UK is likely because it is not such a hub of international travel, and also because the cooperative character of the culture means that many people voluntarily practised social distancing, while many in the US and UK were protesting against its enforcement!

However, given this more cooperative nature of Swedish society, why did they not lock down? Sweden has an admirable constitution, that requires its ministers to listen to the advice of its administrative agencies based on the scientific evidence for different policies. In the absence of clear empirical evidence for a tight lockdown, they used this more relaxed approach and as a result many people died who would have survived if the approaches used in, say, Denmark or Norway were implemented.

The Swedish government policy needed to take into account that the lack of evidence was actually because of a lack of research, which was itself because of a lack of opportunity to research. They should have taken into account the fundamental uncertainty of this situation and therefore pursued a more cautious, “safety-first” approach. Hopefully this highlights the significance of recognising the importance of fundamental uncertainty and factoring it into our models.

Concluding Comments

First of all, I must acknowledge that this reads more like the introduction to a blog than a summary or conclusion. However, the permeation of the erroneous ideas of mainstream economics into the discourse of society about economic life means that it takes considerable effort merely to justify this starting point!

You may now be saying “but what do we do about this”, and I could make specific recommendations. Indeed, this post did offer some tentative suggestions, and this post commented on them further. But my purpose was to give illustrative examples of the practical implications of the ideas in the blog, not to offer a pointless armchair manifesto. I may come back in the future and write a summary section to the blog, drawing out more explicitly the practical implications of each of the points above for the transformation of our economy. This would finally achieve my intended goal – a series of short, easily understandable blog posts that enable anyone to understand the essential features of the functioning of our economy – and I might attempt it just as an exercise in writing.

But the solution to how we create an economy that provides enough for everyone is not a description of a perfect system that we just have to implement, it’s a process of learning for society as a whole. Any process of learning needs to begin with some fundamental axioms or premises, and this is what this post and last week’s offer. In addition, because what is required is a process of learning, the system of education itself becomes fundamentally important, as emphasised last week.

Secondly, I must acknowledge that the informed reader will instantly recognise a considerable overlap between this list and the core elements of the Post Keynesian school of economics. Is this blog just a lot of work to reach the same conclusions as PKE?

From the beginning of my studies I just wanted to know the actual reality of how economies function, and PKE is also relentlessly empirical, so it is no surprise that I have reached similar conclusions. It may seem that I could have saved myself a lot of time by just studying PKE from the outset. But then I wouldn’t have been in a position to assess the value of of PKE if I hadn’t first sought out a wide range of writings on economics focused on empirical fact rather than idealised theory. And channelling myself down a route of just studying PKE would have shut me off from many authors and sources outside of this school – some of the points above get little or no attention in the PKE literature, and this blog could not fairly be regarded as a mere regurgitation of PKE.

For example, my comments on credit above, and the very fact that I start my analysis with the concept of credit, could be straight out of PKE. Yet the author I admire the most in this regard is Perry Mehrling, who wouldn’t normally be considered Post Keynesian, and isn’t even cited in Marc Lavoie’s definitive textbook Post Keynesian Economics: New Foundations (which has 62 pages of references, so it’s a pretty significant omission).

Ultimately, the investigation of economic life should not be a quest to determine which of the various schools is “correct”, but rather to glean from each whatever value it has to offer to a greater understanding of truth. But on that note, I must mention that at time of writing I have nearly finished reading Lavoie’s book cited above, and it is a source of utmost joy. The book is a comprehensive overview of Post Keynesian research, summarising the contributions of the field. There is exquisite beauty in the undeviating use of empirical research and observation as the source of knowledge of economic life. Whereas orthodox economists simply assume, for example, that firms price their products based on marginal cost, thereby enabling them to construct mathematical models that “prove” the supremacy of the market, Post Keynesian economists actually carried out extensive research into how firms price their products, and into the cost structure of firms, and based their theories on the results of this research.

But is this not the essence of what science should be? That this book, and the PKE school in general along with the systems of innovation literature, stand in such contrast to orthodox economics in that they base their foundational assumptions on research into what happens in the real world is, perhaps, the most damning indictment of the failings of that orthodoxy. Like I said above – ideologically driven pseudo-science.

Building an economy that provides enough for everyone will require us to approach our study of economic life with an open and unbiased mind, analysing empirical evidence, and building a body of knowledge based on firm foundations, as proposed in this and the preceding post.

And it requires the participation of each one of us. We are all part of the economy. We all create it together through our actions. And we all have a role in building one that provides enough for everyone.

We all therefore need to base our understanding of the economy on empirically observable facts, not ideology. Maybe someday someone will be able to write a text on the economy that makes these facts accessible to all. Unfortunately, this is currently beyond my writing skills.

Last post 🙁