In this section of the blog I have set out the evidence, in painstaking and indeed painful detail, that financial markets are fundamentally dysfunctional, that they are failing to channel wealth to productive investment, and that they are inherently unstable (hence the constant cycles of boom and bust). There is a need for government intervention in these markets, but what form should this intervention take?

Last week I pointed out that “public ownership” does not only need to take the form of nationalisation – public listed companies benefit from the public’s wealth, channelled through insurance companies and pension funds (ICPFs). ICPFs need to play a far greater role in ensuring that the household savings they manage are channelled to productive investment. This is not going to happen without intervention by public bodies – this is one area where government must play a role in financial markets.

But the idea that government can competently intervene in investment decisions is anathema to mainstream economics, and indeed to all the dominant strands of Western political thought. It is believed that the public sector cannot possibly process and understand all the complex information relating to markets, and indeed that public bodies lack the skills and knowledge of entrepreneurship and innovation.

The remarkable thing is that the historical evidence shows the opposite. Various studies have demonstrated the role the state has played in the development of the internet and “Silicon Valley”, in biotechnology, nanotechnology, pharmaceuticals and renewable energy. Drawing on this and her own empirical research, economist Mariana Mazzucato has produced what may be some of the most important work in economics to date.

Her book ”The Entrepreneurial State: debunking public vs. private sector myths” (2013) sets out the unequivocal facts of this matter with compelling force.

There is a stereotypical cliche that the private sector is the home of innovation – the maverick, genius entrepreneur developing new products that enrich our lives.

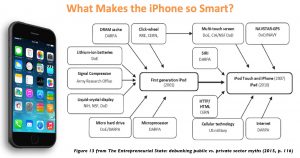

The truth is that most businesses are risk averse, and some of the most important R&D ever undertaken was funded by the Government. The internet, nanotechnology, a whole range of life-saving drugs and vaccines, even the iPhone – none of these would exist had it not been for state-funded research. Mazzucato’s book doesn’t just make vague claims – she repeatedly points out the specific technologies developed through publicly funded research, and the specific sources of funding.

For example, the image below, taken from Mazzucato’s own website , summarises neatly the extent to which the Apple iPhone only exists because of state-funded R&D.

But the role of Government goes beyond funding R&D. Mazzucato outlines the research by various authors that points to the organisational and cultural conditions that need to be in place to enable such breakthroughs to take place. Innovation is not just a question of a single boffin working on a clever idea. First of all there needs to what is called the “basic research” – the breakthroughs in scientific knowledge through research pursuing truth for its own sake, not research into a specific product. Such research is almost exclusively carried out in publicly funded universities and institutions.

Once scientific knowledge is generated, its applications need to be explored. This is known as “applied research”, and again this is largely funded by the public sector, with a small contribution by the private sector. Once ways to apply the science are discovered, products need to be developed and commercially tested. It is only here that venture capital (VC) – which in popular mythology is largely credited with driving the entire process – comes in. VC is looking for short-term investments – once the commercial viability is established the VC will seek to float the relevant company on the stock exchange and thereby make its profits. The new publicly listed company, with proceeds from its flotation, then seeks to bring the product to market and develop capacity for mass production.

But none of these steps happen without the initial publicly funded research, not just in the basic science but in its application. And this knowledge needs to be disseminated through society. This is not a linear process in which one scientific breakthrough will lead to a new product. The advancement of science as a whole impacts entire industries – think of the productivity gains achieved through computing and the internet, technological breakthroughs entirely dependent on the public sector.

So the role of the state is not just to fund the earlier stages of research, but also to shape and create the national infrastructure that will enable industry to make use of this technology. This is referred to in the literature as “the Developmental State” and “systems of innovation”. Investment in nanotechnology, for example, was driven forward by the American Government because it realised that this was a significant and groundbreaking industry of the future and wanted to be at the forefront.

This is, of course, an inadequate summary of Mazzucato’s book and other papers (see in particular her 2012 paper with William Lazonick, “The Risk-Reward Nexus”), but is the best I can do for the purposes of this blog. What I particularly want to emphasise is that, as with the other information on this blog and various economists cited, this work is empirical. Mazzucato has studied the research describing what happens in the real world, and demonstrated powerfully, forcefully and irrefutably the role that the state has played in not just funding research (significant as this is) but in shaping and creating markets.

This has been particularly true in the United States in the second half of the twentieth century, despite the constant rhetoric of small government and minimum state intervention. But in recent years America has started to believe its own rhetoric and to cut back on its spending and intervention, with disastrous consequences for their productivity now and in the future. The vision that drove investment in the internet or nanotechnology has not been there for renewable energies, and this market is now dominated by the Chinese, where the Government has quite rightly recognised the future potential of this industry and backed it significantly.

And there is a final sting in this tail. Corporations often claim that high taxation discourages innovation and investment and even that it deprives them of income that is rightfully there’s. The reality is that it is the public sector that is the sole funder of the vital stages of early research, and private investment only comes in at a later stage (albeit still risky and with much more work to be done – the private sector plays its part). The private sector then goes on to reap the rewards, and the government receives next to nothing. Tax avoidance and tax evasion are depriving governments of their rightful returns on this investment, but in fact even if all profits were honestly declared in the territories where they were earned, the resultant payment of corporation tax would still be less than a reasonable return on the government’s investment. In the jargon of the literature, it’s “socialisation of risk, privatisation of rewards”.

And that’s you they’re not paying back, by the way. It’s your taxes that fund the innovation, and it’s your public services that are underfunded through the failure of the economic system to provide government with its due reward for the contribution it is making to the health of the economy.

And worse still, the decline in government income, massively exacerbated by the recession following the last crash (itself caused by the dysfunctionality of financial markets) means that funding for research is similarly declining, with long term effects on our productivity.

Meanwhile, the dominant public discourse remains that that businesses should be freed from the “shackles” of regulation and taxation, and allowed to get on with their innovating. But the reality is that these companies are profiting from the R&D conducted and paid for by the public sector, with no systems in place that ensure that businesses pay their fair share. Mainstream economic thought utterly fails to recognise this crucial role played by the public sector.

So what can be done? Clearly, there is a need to recognise the critical role of Government in not just funding investment, but in creating and shaping markets. As I have emphasised on this blog, and Mazzucato emphasises in her book, we need to learn, as a society, how to do this. This will take time. There are no single utopian answers or grand plans. The final section of this blog will be on the ideological barriers that prevent us from moving forward.

However, although what is needed is fundamental systemic change, Mazzucato does manage to make some very straightforward, common sense recommendations. For example, it seems a no-brainer that governments should have adequate systems in place to patent the research discoveries they fund and to then license their production, such that they make a due return in royalties. This will require more effective systems in place to track government expenditure on research and how this research has then benefited private companies.

Secondly, rather than giving out grants, governments could give out loans that only need to be repaid when the company turns a set level of profit. Better still, funding could be granted in return for equity. The companies only need to pay anything when they make a profit, but when the next Google or Apple profits from publicly funded research, the Government will reap its due returns. The barrier to such common sense policy is primarily ideological objections to government “ownership” (i.e. shareholding) in private companies. And finally, she recommends development banks, briefly referred to previously in the blog.

Mazzucato’s work is some of the most exciting I have read, which begs the question why I haven’t featured it more prominently or even built the blog more closely around her ideas. And the answer is simply that I only began studying her work in the last few months. When I started the blog I hadn’t read Pozsar’s work, but the theoretical ideas outlined in the opening sections pushed me to search out research in specific aspects of financial markets which lead me to Pozsar. Similarly, when I was writing the posts on Pozsar’s work I hadn’t yet read Mazzucato. But as I continued the research along the lines where logic was leading me it brought me to her work, and I realised I needed to read it to complement my other studies on financial markets. While I found a wealth of material confirming the ideas already expressed in the blog, the profound implications of her findings go beyond what I have presented here, and I will hopefully draw these out in a future section.

It is quite striking to me the number of different economists who, as a result of studying the real world rather than swallowing the mainstream orthodoxy, are reaching much the same conclusions, even though they have not studied each other’s work (which you can tell by checking the references). This is because there are objective facts about the economic world, and there is ideologically driven nonsense. The challenge in studying economics is to learn to tell the difference.